What We Know About ‘The Watcher’ Case Four Years Later

In November 2018, I published a story in this magazine called “The Haunting of a Dream House” about a mysterious stalker who sent creepy and threatening letters to the new owners of a home in Westfield, New Jersey. The anonymous notes were signed by someone calling themselves “The Watcher.” They thanked the Broaddus family for bringing “the young blood” — their three small children — to 657 Boulevard, a home the writer claimed to have been watching for years. The Watcher included details about the Broaddus family and what they were doing at the house: In one letter, The Watcher said they could see the family’s youngest child drawing on an easel in a room on the side of the house. The Watcher suggested they would be keeping tabs on the family and possibly worse: “Once I know their names I will call to them and draw them [to] me.”

The article detailed Derek and Maria Broaddus’s agonizing decisions over what to do about the stalker and the house and their desperate attempts to figure out The Watcher’s identity to no avail. In the four years since the article was published, I’ve gotten a stream of questions — and tips — about the mystery. Spoiler alert: It remains unsolved. But as Netflix prepares to release a limited series based on the story, here’s an update on what’s gone on since 2018.

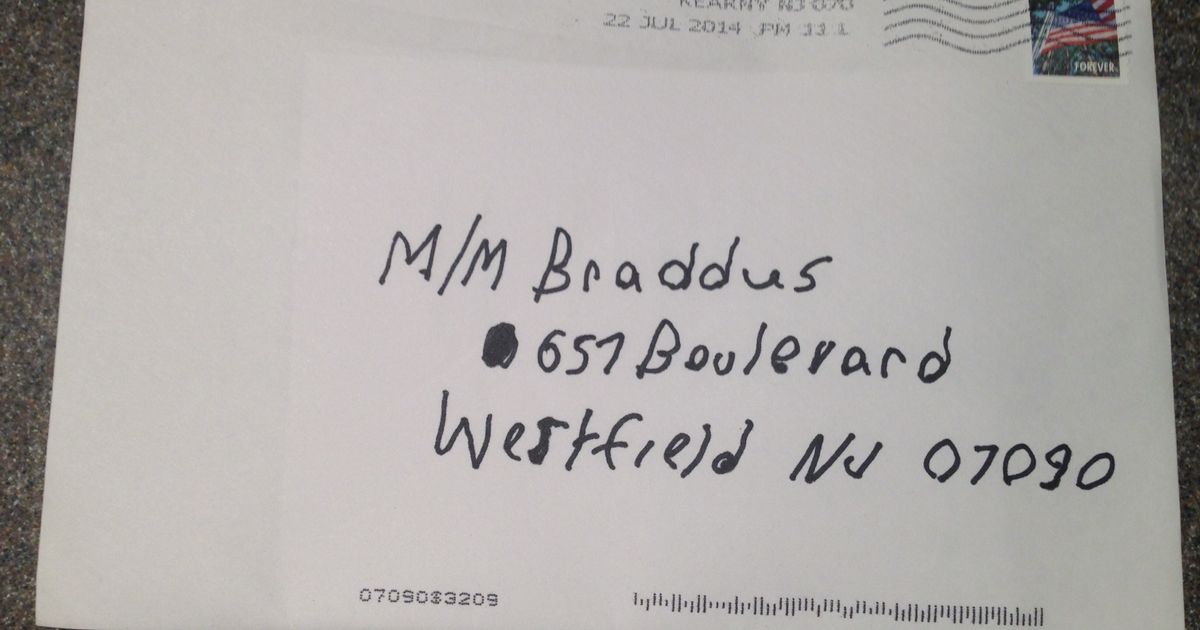

To recap: In June 2014, someone mailed a letter to the new owners of 657 Boulevard. The house had not been listed for sale, yet within two days of the closing, The Watcher was aware that the Woods family had moved out and a new family was moving in. The Watcher knew details about the house — that it had six bedrooms and was approaching its 110th birthday — and expressed angst about the changes new money was bringing to the neighborhood and to the house. They even suggested they had been inside the home decades earlier: “The 1960s were a good time for 657 Boulevard when I ran from room to room imagining the life with the rich occupants there.” The Watcher did not refer to the Broadduses by name in that letter, but two weeks later, a second message addressed them with a phonetic misspelling of their last name — “Braddus” — along with the names of their three young children, correctly spelled and in proper birth order. The Watcher knew the Broadduses were coming and going from the house and that they drove a Mercedes and a Honda minivan.

Each message arrived in roughly similar fashion. The envelope was addressed in a messy handwritten script, but the letters inside were typewritten with “The Watcher” sign-off in a different cursive font. In The Watcher’s third and final letter that summer, they knew the Broadduses were not moving into the home: “Where have you gone to? 657 Boulevard is missing you.”

In March 2019, five years after the Broadduses paid more than $1.35 million for 657 Boulevard, they put it back on the market at a steep discount: $999,000. (From the real-estate agent’s description in the listing: “Endless character and features in this one of a kind home. Must be seen in person!!!”) Their preference was to sell it to a builder who wanted to tear the house down. Eventually, a young family in town agreed to buy it for $959,000 — a loss of roughly $400,000 even before factoring in the agents’ cut (the same agent who sold the house to the Broadduses in 2014 worked with the couple who bought it from them) as well as the $100,000 in property taxes the Broadduses had paid and the bills for utilities, home insurance, the contractors who had begun making renovations to the home, and the lawyers and private investigators they had hired to find a solution to the mystery. A few days before closing, Derek forwarded me an email confirmation of his 60th mortgage payment of $5,495.13 for a house the family had never lived in.

When the sale closed, the Broadduses asked their real-estate attorney to give a note to the new owners. “We wish you nothing but the peace and quiet that we once dreamed of in this house,” they wrote. They attached a photograph of The Watcher’s handwriting in case any new letters showed up.

So far, they haven’t.

In 2015, the mayor of Westfield described the police department’s investigation as “exhaustive,” leaving “no stone unturned.” No one takes that assessment seriously anymore. The police didn’t even speak to some of the immediate neighbors of 657 Boulevard. Later, they rebuffed assistance from several investigators the Broadduses hired — including a retired NYPD officer, a forensic linguist, and a former FBI agent who could make an introduction to the agency’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. In 2018, amid several unrelated scandals, Westfield’s chief of police retired. Barron Chambliss, a former Westfield police officer who reinvestigated the case a year after the incident took place, was blunt in his critique. “I’m not Sam Spade, but the Westfield Police Department fucked these peoples’ case up,” Chambliss told me recently. (The Westfield police did not respond to requests to discuss the investigation.)

Eventually, the case was turned over to the Union County Prosecutor’s Office, which started its investigation from scratch. “This is not necessarily a case the prosecutor’s office would be involved in,” Vince Gagliardi, the former chief of detectives for the prosecutor’s office, told me recently. “Our lane is homicide, narcotics, financial crimes — not this stalking stuff.” By 2018, the office had put considerable resources into the investigation, but without fresh evidence or new leads, they had largely stopped working on the case.

A few weeks after our article was published, the prosecutor’s office decided to try one more new idea. A forensic investigation had found saliva on the underflap of one of the envelopes, and subsequent DNA analysis determined that the letter was apparently licked shut by a woman. (Several early suspects had been ruled out by DNA samples that didn’t match.) In December 2018, the prosecutor’s office canvassed the neighborhood again; this time, it decided to ask everyone on the block to voluntarily submit DNA samples for comparison.

A month later, the Broadduses were called to a meeting at the prosecutor’s office in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The Broadduses were told that, by and large, the neighbors were cooperative. No one was eager to appear suspicious. But none of the swabs matched the sample from the envelope.

The Broadduses begged to know more: How many people had given samples? Who had been ruled out? Several people on the block later told me they weren’t home during the canvas, and according to a person close to the investigation, two people refused to have their cheeks swabbed, at least one of whom was a “close neighbor” of 657 Boulevard and someone the police had considered as a suspect. But the prosecutor’s office declined to elaborate.

The Broadduses pitched one more idea: forensic genealogy. The emerging (and controversial) field involves using the DNA that millions of people have uploaded in pursuit of genetic and ancestral enlightenment in order to triangulate criminal suspects through their relatives. Some researchers believe that roughly 90 percent of Americans of European descent can now be identified based on DNA uploaded to these databases. (Westfield is 82 percent white.) The technique has been used in an increasing number of cold cases, and Derek connected with a company that was willing to take a look at the case if the prosecutor’s office would share the DNA. But the prosecutor rejected the idea, arguing that the office had never used the technology before and could not justify doing so for a family that received a few threatening letters when it had unsolved murders and rapes to deal with. The Broadduses offered to cover the costs of using the technique on their case, and several of those cases, but got nowhere. They were told that, in the absence of new evidence, there wasn’t much more to do. In an email to me after the meeting, Derek said, “We lose again.”

The prosecutor’s office declined to comment on the case, saying that while the investigation isn’t active, it isn’t closed.

At least one person was. After the canvas, an anonymous writer sent an email to several local officials. “What gives the authority to the Prosecutor’s Office to go door to door and demand DNA samples of residents without a warrant or Judge’s order?” the author, who identified himself as Malcolm Mannix, wrote. “Even if the Watcher is caught, what laws will they be charged with and what jail time will they really face? Is this the best use of the Prosecutor’s resources?” (Mannix’s answer to the last question: “pursuing illegal aliens.”)

Who is Malcolm Mannix? There wasn’t anyone with that name in Westfield. Mannix was a TV show that first aired in the 1960s, in which Lieutenant Art Malcolm helps private detective Joe Mannix solve crimes — which meant that someone near 657 Boulevard who appeared to have a working knowledge of ’60s pop culture had written an anonymous email complaining about an attempt to unmask The Watcher. Several messages to Mannix’s email address bounced back.

This isn’t new, but it has not been published before: This is what The Watcher’s handwriting looks like, as seen on the third letter sent to 657 Boulevard.

If the police were running out of ideas, our readers had plenty.

Did anyone check the letters for fingerprints? Yes, but there wasn’t anything usable. What about the neighbor who walked up to Derek and told him they were excited to have some “young blood” in the neighborhood? There wasn’t anything to rule them out, but there wasn’t anything else to rule them in. And how about a disgruntled mail carrier — someone with a regular view of the house and pent-up anger about the rising wealth on their daily route and the increase in package deliveries that came with it? Frank Shea, the Broadduses’ private investigator, told me the United States Postal Inspectors had looked into the case and that several Postal Service employees were interviewed. “They were just as confused as anybody else,” Shea said. (The Postal Inspectors did not respond to a request for comment.) Cameras were installed at the local post office as well as at the library, where someone might use a computer to type out an anonymous letter. No luck.

Several readers tried to identify a literary inspiration for the letters and suggested a subpoena of library records to find someone familiar with the work of Shirley Jackson, or the novel Watching You, published just a few months before The Watcher’s letters and narrated by a stalker. (“I am the one who watches.”) One reader saw echoes of Dean Koontz in The Watcher’s “care for language, and in their ultimate effect — the disturbance of the social fabric of an entire town.” As it happens, Koontz published a novel called Watchers in 1989.

The closest literary connection anyone could draw was a short story from the 19th century by J. Sheridan Le Fanu, an Irish author of Gothic mysteries. The story follows a Mr. Barton who goes mad after receiving a series of threatening letters at his home sent by a writer using the same pen name:

Mr. Barton … is warned of danger. He will do wisely to avoid —— Street … if he walks there as usual, he will meet with something bad. Let him take warning, once for all, for he has good reason to dread.

The Watcher

All of this was fun to speculate about, but the leads were starting to stretch thin. At one point, a Westfield official suggested a suspect with the following profile: a man who lived down the street from 657 Boulevard, was a member of the local historical society, and liked to write letters — specifically, lengthy year-in-review holiday emails to friends and acquaintances. The Broadduses’ forensic linguist took a look but didn’t see any definitive overlap in the writing style. When I called the suspect in question and asked if he was The Watcher, he gave a hearty laugh and said the only concern he’d given to the whole thing was whether it might depress property values on the block.

The most intriguing new theory I heard involved a local teacher. For 33 years, Robert Kaplow taught English at Summit High School, two towns over from Westfield. Kaplow built a career as a writer and was best known for short comic bits he performed on NPR under the name Moe Moskowitz, of Moe Moskowitz and the Punsters, and for his 2003 novel, Me and Orson Welles, which Richard Linklater adapted into a movie. The novel is filled with references to Westfield, where Kaplow grew up in the 1960s. “Westfield remains for me the geography of my youth,” Kaplow said in 2009. “I’m still very drawn to the place.”

Over the years, Kaplow had told a story to his students that now struck many of them as curious. The story was about a particular house in Westfield and Kaplow’s obsession with it. “He had this idea to start writing letters to the house — not the occupants but to the house,” a former student told me. Another student recalled Kaplow saying that he had sent more than 50 letters to the house in question.

There were other odd connections. Kaplow retired in 2014 and finished his final semester of teaching that June — the same month The Watcher started sending letters to the Broadduses. And while Robert had moved out of Westfield, his brother, Richard, was still there: He lived half a block from 657 Boulevard and worked as an attorney in town. In fact, when the Broadduses sued the Woods family, alleging that they should have disclosed the letter they’d received from The Watcher, the Woodses were represented by — you guessed it — Richard Kaplow.

“There’s nothing there,” Robert told me recently after I relayed the speculation from the AP English rumor mill. He said that he was familiar with the accusation. He had read about it on Wikipedia. In 2020, a user updated Kaplow’s page with a paragraph detailing the evidence. An editing war ensued. The insinuation was removed as defamatory, then reinserted and deleted and reinserted several more times. Last year, a user in New Jersey declared: “Due to this circumstantial evidence, one person who continually edits Kaplow’s Wikipedia page believes that Robert Kaplow is ‘The Watcher.’” Kaplow admitted that he had written letters to a house in Westfield, as his students recalled. But the house wasn’t 657 Boulevard. He said it was a Victorian on the north side of town and the letters were admiring, not threatening. He eventually befriended the family who lived there; they even let him housesit once.

Most of the professional detectives who have looked at the case agree on a few things: The Watcher most likely lived near 657 Boulevard, and they were probably an older person. Much of the initial investigation focused on members of two families who lived immediately around 657 Boulevard and fit the profile. The Broadduses were told that DNA samples obtained from several of these suspects weren’t a match. Of course, DNA evidence isn’t foolproof. But short of a match, there isn’t much hope for a resolution other than a confession. In the past few years, several of the early suspects have died.

One of the questions I’ve gotten most was a version of this one: Did the family do it? Even people who recognize the theory’s implausibility still seem titillated by the notion. But it makes no logical sense. If this was a nefarious plot, it was ill-conceived in a spectacular way, to no clear practical end, with the only result being the self-sabotage of years of the Broadduses’ lives. “Maria was distraught every time I saw her. She was shaking,” Vince Gagliardi, who investigated the case for the prosecutor’s office, told me. “I can tell you this: If Maria Broaddus was faking, she should play herself in the movie.”

Westfield has a history of embracing its scary side. Pretty much everyone I spoke to in town asked me if I knew about John List, who’d murdered his wife, mother, and three children at their home in Westfield in 1971. And this month, the town kicked off its fifth annual Addams Fest, in honor of Westfield native Charles Addams, who’d used a Victorian house in town as the model homestead for his cartoon family of misfits and monsters. A day after The Watcher adaptation is to be released on Netflix, downtown Westfield will host “Morticia and Gomez’s Masquerade Ball.”

But unlike the Addams family, this case was real, and unlike List’s victims, the Broadduses still live in Westfield. As I surveyed locals, I found plenty of sympathy for the family and what they had been through, but a surprising number of people seemed to harbor resentment about all of the attention the case had brought to the town or still believed the Broadduses had done this to themselves. “The Charles Addams thing — all that haunted-house bullshit — it’s used to bring people together,” Gagliardi, from the prosecutor’s office, told me. “With The Watcher, there is nothing I’ve ever seen in this town as polarized as this. Everybody’s got an opinion.”

Gagliardi lives in Westfield, and while he didn’t know the Broadduses well, he and Maria had served on the kindergarten parent-teacher organization together. He retired in 2019 and declined to discuss details of the investigation on the record, but when we spoke recently, he told me that a memory of the town’s treatment of the Broadduses came rushing back and made him “absolutely furious.” In January 2019, while the prosecutor’s office was still sorting through its DNA canvas, Gagliardi attended the swearing-in of Westfield’s new police chief. Beforehand, the town board had announced that it would be giving out awards in Westfield’s annual holiday gingerbread-house contest. Gagliardi was shocked as he watched first prize in the Iconic Building category go to a rendition of 657 Boulevard, complete with The Watcher’s letters sitting on the front porch. “I’m saying to myself, If I’m the Broadduses, do I really think that Westfield is taking this seriously?” Gagliardi told me.

Gagliardi was even more upset by what happened next, when the new police chief stood up to give a speech. “In front of a packed hall, he thanks me for coming — ‘Even though you and your office can’t solve The Watcher case,’” Gagliardi told me. Everybody laughed except him. “We had all these drag-out meetings with the Broadduses, and my office was giving everything we possibly could,” Gagliardi said. “You can’t say, ‘We’re taking this seriously as a community,’ then have something like this in a public forum. I’m not talking as the chief of detectives. I’m talking as a general fucking human being.”

Most people in Westfield told me they have moved on. The Watcher is a story they get asked about when people find out where they live or a house where teens can dare each other to run up and take a selfie on the doorstep at Halloween. Soon, it will be something to binge.

Eight years later, The Watcher still has a way of infecting their lives; there are reminders of the situation all around town. (The Broadduses still live in Westfield in a lovely, albeit smaller, house.) Derek admits to having had a difficult time getting beyond his obsession with the case and what it did to their lives. “I had just turned 40 when we bought the house,” he joked to me a few years ago. “I am now 93 years old.” But the Broadduses try to avoid thinking or talking about The Watcher, which only adds stress. They prefer to move on and have turned down offers to go on just about every television network and declined interest from documentarians hoping to try and solve the case, not wanting to put their lives on-camera.

Pretty much everyone I spoke to in Westfield believes the Broadduses made a killing by giving Netflix the right to adapt their story. One neighbor told me she’d heard that the Broadduses pocketed close to $10 million. In reality, the money from Netflix didn’t even cover their losses on the house.

In 2018, a number of major film and TV producers expressed interest in acquiring the rights to adapt our article and their life story — one horror producer offered to buy 657 Boulevard, hoping to use the house as a set. The Broadduses had little interest in giving someone the right to make a piece of entertainment out of the worst years of their life, but they had prior experience with Hollywood telling their story even without their permission: In 2016, Lifetime released a movie called The Watcher with enough artistic license — the film’s couple is biracial, and the letters come from “The Raven” — that the Broadduses couldn’t halt its release.

Selling the rights offered a modicum of control, although the Broadduses wanted little involvement. They made only two requests and a suggestion to the production team: that the show not use their name, that the onscreen family look as little like theirs as possible (Naomi Watts and Bobby Cannavale have two kids rather than three), and that they wouldn’t mind it if the fictional house burned to the ground.

The Broadduses have not seen the show. Derek doesn’t plan to watch it. Seeing the trailer was stressful enough.

At this point, there seem to be only two possibilities: a confession or a DNA match.

In 2020, the Broadduses asked the prosecutor to close the case and return the letters and DNA evidence to them, so that they could hand it over to the forensic genealogists themselves. The office declined to do so. The Broadduses say their offer to pay for the forensic genealogy in their case, and several others, still stands.